Understanding the journey

A researcher studies lesser scaup migration and uncovers every duck has its day…to migrate.

Sixty-two years ago, North America’s most ambitious wildlife survey was hatched. The overriding goal of the Waterfowl Breeding Population and Habitat Survey (WBPHS) was to collect data on mallards, the continent’s most common (and commonly hunted) waterfowl species.

Since then, the Canadian Wildlife Service (CWS) and United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) have flown this survey annually to coincide with greenhead migration, identifying and counting every migratory waterfowl species they see.

The information they collect from the air (combined with ground surveys) is used to estimate breeding populations, monitor trends, set harvest regulations and inform waterfowl management and conservation initiatives, like the North American Waterfowl Management Plan.

“It’s awesome that we have this data,” says Taylor Finger, a migratory bird game ecologist with Wisconsin’s Department of Natural Resources. But for years, Finger and other waterfowl biologists like him, wondered, do these aerial counts accurately count other duck species?

It’s an important question to ask.

The survey isn’t designed to collect accurate counts of sea and diving ducks, species with different migration strategies than mallards, notes Taylor and the USFWS website.

An early nesting species, mallards migrate promptly and quickly. For ducks like lesser scaup, however, migration is believed to be more variable.

To better understand lesser scaup migration, and learn if this species was being accurately counted by WBPHS surveyors, Finger participated in a five-year study (2005-2010).

As a graduate student at Western University, he looked at how environmental conditions (temperature, precipitation and ice cover) impact lesser scaup arrival to and journey through areas in the WBPHS catchment.

The research

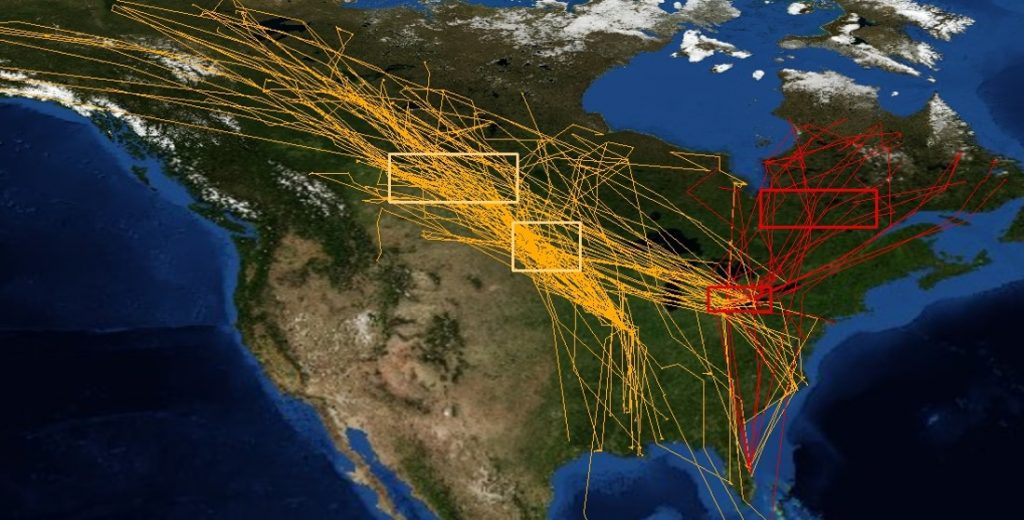

The WBPHS covers an area roughly the size of Nunavut and Quebec, combined. It’s broken into two regions, and 77 strata.

The “traditional” survey area captures migration through central, western and parts of northern Canada, as well as the Dakotas, Alaska and Montana. The “eastern” survey area, encompasses eastern and Atlantic Canada, as well as Maine.

To understand how environmental conditions might influence lesser scaup migration to and then through the WBPHS areas, Finger had to track the movement of individual birds.

As part of the study, a team had to capture and outfit 78 lesser scaup hens with satellite transmitters, at three different locations in the United States and Canada.

Transmitters have the potential to bias data by altering how the species they’re attached to (or in this case, embedded in) behave.

To test for this, Finger compared the movements of his study subjects to lesser scaup migration data collected by North Dakota Fish and Game (NDFG). Finger’s birds were migrating normally.

By tracking the movement of these marked birds and collecting environmental data at four different locations within the two WBPHS survey areas, Finger learned weather conditions impact lesser scaup migration…sometimes.

The findings

Finger found temperature and increased rainfall influenced lesser scaup arrival and migration through the WBPHS traditional survey area.

Migration through this area generally occurred earlier and faster with warmer temperatures, increased spring rainfall and decreased ice cover.

In colder years, when there was less available habitat, lesser scaup migration journey was slower. This is likely because diving ducks need open water to land on and forage in.

“It makes sense, but [previous to this study], we didn’t have any data to show that,” says Finger.

Something that did surprise this researcher, was lesser scaup migration through the WBPHS eastern survey area.

Regardless of weather, lesser scaup outfitted with transmitters arrived to this survey area from their wintering grounds earlier, remained there longer, and migrated to their breeding grounds later and more quickly.

“These birds would sit around even though the conditions were good to migrate. But when they want to be on the breeding grounds, they’ll fly a couple thousand kilometers in a few days,” says Finger.

He says more research is needed, but suggests the near constant availability of food from the Great Lakes may be a factor.

What it all means

Finger’s research proves a long-held belief to be true. Lesser scaup migration through the WBPHS traditional and eastern areas is variable. In the case of the traditional survey area, at least, this variability is linked to weather conditions.

By monitoring lesser scaup migration over a five-year span, Finger uncovered that the WBPHS, designed to coincide with the migration of mallards, is likely not accurately and consistently capturing the number of lesser scaup.

Despite the survey’s limitations, Finger recognizes its value. “It’s a great tool to look at trends over time,” he says. “But if you’re looking at it to count every lesser scaup in the country…I wouldn’t recommend it.”

Finger’s research earned him the 2016 Institute for Wetland and Waterfowl Research (IWWR) Student Publication Award. This award is given to raise awareness of the IWWR student program, reward students for successfully publishing their research, and to recognize publications that make a significant contribution to waterfowl and wetland research.