The Side-Effects of Stress

Arctic researchers link stress experienced during moult to mortality

Life can get a little crazy for all of us, from time to time. It’s not unusual for sleep, a healthy diet and exercise to fall to the wayside. Everything’s fine for a little while. Until, it’s not.

Eventually, we burn out. Then, a cold, flu, or some other virus comes along and knocks us to our knees—or more often, to the nearest couch or bed. Sound familiar?

It’s been scientifically proven that stress affects our well-being, and humans aren’t the only ones to feel its effects. “There are these multiple, continuous factors that are going to impact your health and the same goes for birds,” says Jane Harms, now a veterinarian with Environment Yukon.

Harms led a study that explored the cross-seasonal effects of stressful moulting periods on Arctic migratory birds. This innovative PhD work earned her an Institute for Wetland and Waterfowl Research’s (IWWR) fellowship, which supported her efforts from 2011-2013. On top of this, her subsequent research paper earned her the 2015 Ducks Unlimited Canada IWWR Student Publication Award.

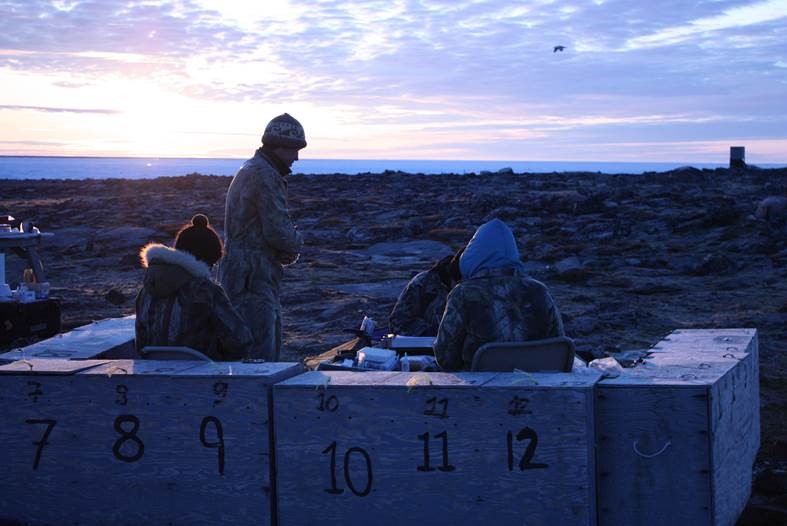

By analyzing tail feathers collected from common eiders at nesting grounds on East Bay Island, Nunavut, over a five-year period (2007-2011), Harms and her colleagues learned that birds who experience stressors during moult arrived to breeding grounds later, and were less successful at producing a clutch of eggs.

“The interesting thing about carryover effects… is that we know from ourselves that our particular health isn’t just what’s happening to you at this moment. It’s influenced by everything from who your parents are to what you eat and how you eat it,” says Harms.

Or, in the case of Arctic waterfowl: how your moult went.

Moulting is a process that all waterfowl species go through at least once a year. It sees them losing their flight feathers, and growing new ones in their place. And it’s one of the most energy-taxing activities waterfowl experience, second only to producing a clutch of eggs.

Birds must consume a great deal of protein-rich food (like invertebrates) to meet the nutritional demands of a moult, as well as to give them the energy they need to avoid predators, and other threats. A stressful moult (caused by outside factors, like predators and poor habitat) can result in a bird growing shorter flight feathers, which makes travel more difficult, and tiring.

Feather analysis research and new technology has helped researchers like Harms better understand the effects difficult moults have on waterfowl.

Unlike other body tissue, feathers develop in a relatively short span of time and once they’ve finished growing, they become metabolically inert. By collecting feathers from waterfowl on Arctic breeding grounds and later analyzing them, Harms discovered birds with elevated corticosterone levels (a hormone the body produces to manage stress) were the same birds who were less successful during the nesting period.

But that’s not all. Common eiders who experienced a stressful moult were also 30 per cent less likely to survive an avian cholera outbreak.

First identified in Canada in the 1940s, avian cholera is a bacterial disease that’s resulted in substantial mortality among common eiders on East Bay Island, since its detection there in 2005. “Avian cholera on East Bay Island has caused annual eider mortality, and adult eider survival rates and reproductive success [to plummet] since the first confirmed outbreak,” writes Harms, in a 2012 article published in Arctic.

The deaths have had a negative impact on the northern ecosystem, as well as on local Indigenous communities. “Eiders are a very important species for Inuit in the north,” says Harms, noting some communities rely on the birds for their eggs, down and skin.

According to Dale Wrubleski, a DUC research scientist who chaired the IWWR Student Publication Award committee, Harms’ research shows that a healthy bird is better equipped to handle the stress of life events. “We [DUC] don’t manage disease, but in some ways we do: by providing good habitat,” says Wrubleski.

“Outbreaks are going to occur from time to time. If the habitat is in good condition during these other life history events, like moulting, birds are better able to withstand things like avian cholera outbreaks.”

Jane Harms was the recipient of the IWWR Bonnycastle Fellowship in Wetland and Waterfowl Biology from 2011-2013. She is also one of two recipients of the 2015 IWWR Student Publication Award. This award is given to raise awareness of the IWWR student program, reward students for successfully publishing their research, and to recognize publications that make a significant contribution to waterfowl and wetland research.